Deep dives

Deep dives explore the implementation of selected recommendations or thematic areas in more detail to understand the strengths, challenges and early insights of implementation observed on the ground.

The purpose is to highlight early implementation learnings, opportunities for continuous improvement and examples of best practice and innovation.

Insights from deep dives are examined alongside adequacy assessments and individual recommendations to understand how the 4Cs of implementation (Collaboration, Coverage, Consistency, Communication) are operating in practice.

To date, the IIS has conducted two deep dive discussions, provided in the fourth progress report (May 2024).

Background

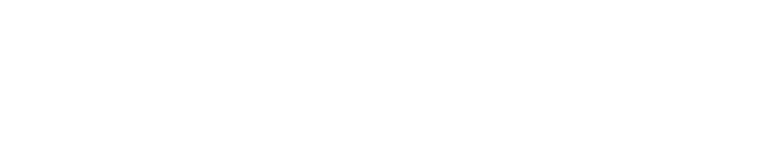

High Risk Teams (HRTs) consist of a team of representatives (‘HRT members’) from government and non-government services who, led by a specialist DFV non-government organisation, work together to coordinate responses to DFV identified as having a high or imminent risk of serious harm or lethality.

HRTs provide for more coordinated and holistic service delivery to support victim-survivors of DFV where an urgent and targeted service response is required.

Purpose of the deep dive

In response to Recommendation 18 of Report One the Queensland Government committed to roll out three new HRTs. Implementation is being phased over four years to 2025-26, with the first new HRT rolled out in Townsville in 2023.

Recommendation 18 of Hear Her Voice Report One:

’The Queensland Government continue to roll out integrated service system responses and High-Risk Teams in additional locations. Further rollout of these responses will build upon the lessons learned to date and will be informed by the outcome of the evaluation undertaken in 2019 and any developing evidence base.’

The OIIS examined the progress of implementation for the new HRT six months after referrals commenced. The IIS spoke with HRT core agency representatives, other staff in the core agencies and external services in the region to identify lessons learned that could inform implementation of HRTs in the future.

Implementation insights

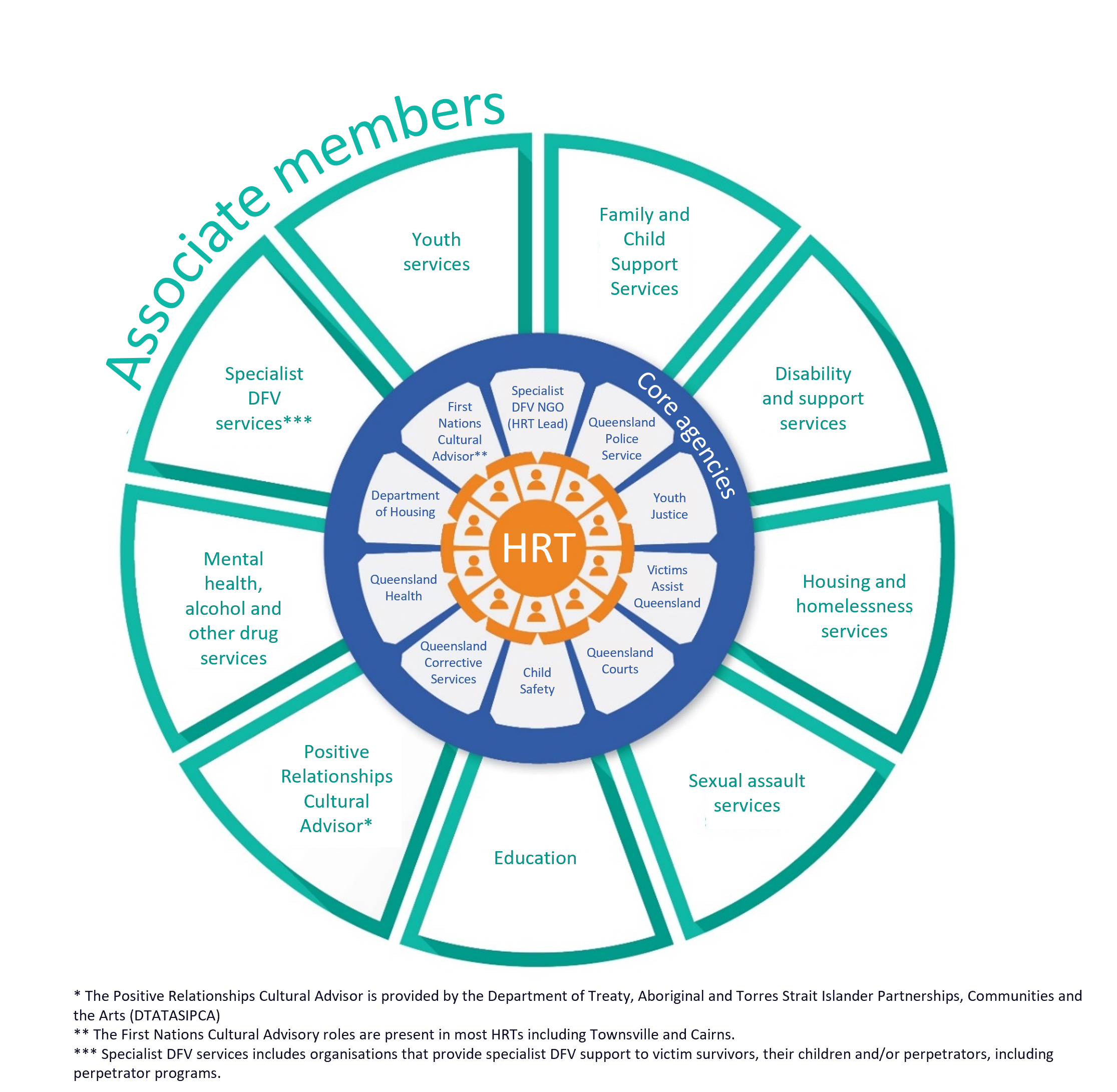

The Townsville HRT has shown strong progress in its first six (6) months of operation and stakeholders involved continue to demonstrate a high level of commitment and dedication to ensuring the team’s ongoing success.

The implementation learnings from the deep dive into of the Townsville HRT will help to support the continuous improvement and expansion of HRTs in Queensland and the IIS has proactively shared these learnings with officers involved in the roll-out of new HRT in Redlands and in planning for the future roll-out in Rockhampton.

Background

In Recommendation 11 of Report Two, the Taskforce recommended the Queensland Government ‘co-design, fund and implement, a victim-centric , trauma-informed service model for responding to sexual violence’.

The Taskforce provided several important considerations the service model should follow, including that they involve services and agencies working together in an integrated way to meet victim-survivors’ needs.

In response to Recommendation 11 of Report Two, the Queensland Government committed to ‘co-design a victim-centric, trauma-informed service model for responding to sexual violence, similar to the SART, and implement the model in additional locations’. The type and locations of the future models are yet to be announced, with discussions still underway.

The OIIS met with the SART in Townsville and a number of sexual assault services to understand the enablers and challenges to building coordinated and integrated service responses to sexual assault. The purpose was to identify any key implementation learnings that could help inform the expansion of SARTs, or other multi-agency models for sexual assault, in other Queensland locations.

The Sexual Assault Response Team (SART)

Established in July 2016, the Townsville SART (the SART) responds to the need for a more integrated response to victim-survivors of sexual assault. The SART is led by the Women’s Centre, a specialist sexual violence NGO, and consists of representatives from the Women’s Centre (including a Sexual Assault Support Service (SASS) worker), Queensland Police Service, several departments from Queensland Health and the Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions.

The SASS worker provides ongoing support for the victim-survivor from the point of presentation through to police statements, clinical forensic medical examinations, general medical support and the criminal justice process. This supports the victim-survivor throughout their journey regardless of the length of their matter, noting that many matters run for several years.

Enablers identified for successful implementation of a SART included:

- the model structure is formalised in a Terms of Reference that is adaptable and co-designed by all core agencies, with victim-survivors remaining at the centre,

- the SART principles and practices are embedded and endorsed in each agency’s internal systems,

- a commitment to reflective practice endorsed within each broader agency, and

- the presence of a specialist sexual violence NGO within the core SART membership from the outset.

Supporting consistency of the core model components is an important consideration as SARTs expand to other regions, to ensure alignment with evidence-based, best-practice principles on responding to victim-survivors of sexual assault.

Considerations for implementation of future multi-agency responses to sexual violence

The Taskforce highlighted the SART as an example of a multi-agency model that could potentially be replicated elsewhere, but it did not specify the future models should be a SART specifically. Regardless of the type of model employed, from SARTs to more informal approaches, consultation revealed that several challenges exist which will require consideration in the development of any new multi-agency service model.